|

In the west, the animation and comic book industries are only slowly beginning the earn the same respect that they have had in Japan for half a century. Dominated by Disney and superheroes, animation and comics are seen largely as the domain of children and virgin geeks. Despite this, much significant headway has been made into animation and comics as a medium for storytelling rather than as a children's genre... Even breakthrough live-action adaptations like Spider-Man are enjoyed more as a kitschy youthful reminisce than as genuine art. Comics like the World War II epic Maus and the animated film Prince of Egypt are changing minds. In Japan, however, the period of comic and animation being seen as "kid's stuff" was relatively short. Throughout most of the history of the industry in Japan, animation and comics have been seen as a perfectly valid form of art and storytelling, enjoyed by people of all ages and from all walks of life. Anime and Manga (animation and comics, respectively) tell all kinda of stories across the full breadth and depth of genres, from science fiction to drama, from fantasy to horror, from children's stories to pornography. Why is this so? Japanese newspaper Asahi points to none other than Osamu Tezuka himself as the cause: "Foreign visitors to Japan often find it difficult to understand why Japanese people like comics so much. One explanation for the popularity of comics in Japan, however, is that Japan had Tezuka Osamu, whereas other nations did not. Without Dr. Tezuka, the postwar explosion in comics in Japan would have been inconceivable."

Nestled within the expanses of JR Kyoto Station in Kyoto, Japan, is the Tezuka Studios shop and exhibit. A testament to Tezuka's creative genius, this shrine is stocked with a complete set of his works, framed art chronicling his career, and a viewing room for short films every half hour. And, of course, a shoppe in which to buy anything you could want with Astroboy on it.

|

Osamu Tezuka has long been regarded as the "God of Manga". Working in the field of Japanese comics since the 1940s (saddly he passed away in 1989), Tezuka is almost single-handedly responsible for the familiar look of Japanese animation, most notably the distinctly large eyes. Over his half-century of work in the industry, Tezuka has created many characters that are familiar to western audiences, including Black Jack, Princess Knight, Kimba the White Lion, the recent film Metropolis, and most famous of all, Astro Boy. Osamu Tezuka has long been regarded as the "God of Manga". Working in the field of Japanese comics since the 1940s (saddly he passed away in 1989), Tezuka is almost single-handedly responsible for the familiar look of Japanese animation, most notably the distinctly large eyes. Over his half-century of work in the industry, Tezuka has created many characters that are familiar to western audiences, including Black Jack, Princess Knight, Kimba the White Lion, the recent film Metropolis, and most famous of all, Astro Boy.

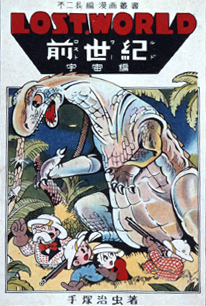

Beginning his career in 1946, Tezkua skyrocketed to fame with his 1947 The New Treasure Island. In post-war Japan, manga (Japanese comics) was a very small, child-oriented niche market. Despite this, New Terasure Island sold over 400,000 copies... An unthinkable number. This success was duplicated with his 1948 version of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World. Though constantly reprinted in Japan, Tezuka's The Lost World is almost entirely unknown in the west. However, the recent success of another resurrected Tezuka project has seen a renewed interest in his older work. In 2001, the spectacular anime feature film Metropolis was released, based on a manga Tezkua had created in 1950. The manga itself was based very very loosely off of Fritz Lang's 1927 silent film Metropolis, but the storyline was radically changed. This manga, with it's themes of futuristic cities and android robots, would become something of a trial run for Tezuka's most famous creation, Astro Boy. Anime producer Rin Taro, who worked on the Astro Boy television animation, brought this 50 year old work of Tezuka into the modern consciousness. The relative success of Metropolis has in turn provoked Dark Horse Comics to publish Tezuka's earlier works, including Astro Boy, Metropolis, and now, The Lost World. The Lost World which the reader finds in Tezuka's manga, however, is a Lost World unlike any other. Not an adaptation, this is a complete reimagining of the story. Tezuka himself attests to this decided split from the original tale: "As for the title, it has no relation whatsoever to the Conan Doyle novel of the same name. In much the same way as Metropolis, which came later, at the time I hadn't even read Doyle's Lost World. I just thought it was a cool title for some reason, so I partook of it." Fair enough, Mr. Tezuka. Unlike other novels which used the title of the classic tale, Tezuka didn't trash the source, and his version has a certain charm all its own that still makes it worthy of inclusion in the catalogue of Lost World tales.

Along the way we encounter a healthy dose of hard boiled detectives, Dr. Moreau style experimentation, secret criminal organizations, a new race of plant people, turn abouts, betrayals, graphic murder and beatings, and oh yes, dinosaurs as well! And all in one childrens' story. About the most difficult thing for Western readers to grasp about Lost World is the nuances and values it inherits from the mid-20th century Japanese culture it came from. The humour in it is sometimes baffling, and things happen that one can only guess are some culture's idea of funny. In comics, according to Scott Macleod's Understanding Comics, the true action and the involvement of the reader come in between the pannels, when the reader bridges the motion gap from one picture to the next. Tezuka's work feels often like it is missing a pannel, leaving the reader to fill in too much, especially if the reader isn't from his culture. Also, as alluded to by the mention of murder and beatings, Lost World seems shockingly graphic for a childrens' story. It is graphic both physically in the violence present and emotionally as the characters deal with the ramifications of the violence. The story even ends with one of the main characters mourning the loss of his little friend. What is so disarming about all this is that Tezuka's style is very cartoony and suited to children. Imagine an old 1930s Mickey Mouse cartoon with hatched lines trailing the bullet that made a big hole in Peg-Leg Pete. Such is the culture, though, and Tezuka's story teaches children values consistent with his society just as our cartoons and comics teach children values consistent with ours. as oriented towards children as Lost World is, it is not just a childrens' story. One of the reasons that manga is so popular in Japan is because of Tezuka's innovation in making his books not only appealing to kids, but to adults as well. And for fans of The Lost World, Conan Doyle's variety, this take on the concept from across the Pacific is certainly an interesting exercise.

|