|

The craft of stop-motion animation is well-known by this time. Formerly the only way to successfully realize fantastic creatures of fantasy worlds and bygone ages has been supplanted by computer generated imagery, reserving stop-motion for more specialized and stylized art films by the likes of Tim Burton and the Brothers Quay. One great advantage that stop-motion has over most CGI, though, is that stop-motion has actual physical presence. Unless it is exceptionally well done (and few examples are), CGI tends to look flat and lacking in dimensionality. Stop-motion utilizes actual physical models that occupy actual physical space, and so look at least that much more real. In the case of The Lost World, the models were ball-and-socket dual armatures, upon which foam musculature, detailed latex skins and assorted protuberances and plates were applied. These models crafted by Marcel Delgado were far more complicated than the clay, wire and cloth models previously employed by Willis O'Brien for his shorts and Ghost of Slumber Mountain. Many of these miniature dinosaurs included complicated mechanical effects to add realism, such as an air bladder to simulate breathing. For the most part, the models were just over a foot long, depending on the relative size of the dinosaur it was supposed to be. Numerous scale sets had to be built for the dinosaurs to stomp around in as well. Most ambitious was the massive 150 feet long plateau landscape used in the climactic dinosaur stampede sequence. The very fact that The Lost World's stop-motion was primitive and pioneering gave it an unexpected advantage when looking back upon it now. With O'Brien's craft being much improved by the time he made King Kong, he was better able to integrate the human cast and the dinosaurs... resulting in the advent of the movie monster who seems to exist for no purpose other than terrorizing the protagonists. Because this was not possible when The Lost World was made, the dinosaur scenes tend to be ones of dinosaurs attacking eachother while the characters look on. Many scenes from the book had to go unrealized (like the pterosaur rookery), but in their place was, for all intents and purposes, a dinosaur documentary showing prehistoric monsters in actual ecological conditions.

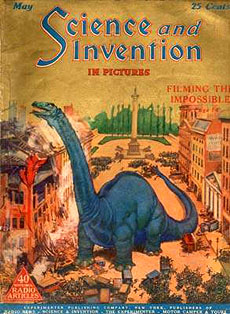

A 1925 issue of the magazine Science and Invention featured an article on Willis O'Brien's stop-motion magic.

Bull Montana's arduous work as the Ape Man involved a 4am make-up session every day, but it was worth it. The Toronto Star remarked that: “The marked resemblance of an ape is achieved at tremendous expense and labor. Every bit of the make-up is given the greatest care and attention. Many people who watch the real and the pseudo ape in 'The Lost World' fail to distinguish one from the other.” (April 18, 1925) You can see Bull without his make-up, though, in the Penny Arcade of Disneyland's Main Street USA. In one of their exquisite collection of antique movie machines (and a functioning, coin-opperated orchestrion), Montana plays a boxer who pumels a poor, sickly-looking comedian.

The Lost World wasn't Wallace Beery's first time tussling with dinosaurs. In 1923, Beery played the nemesis of slapstick comedian Buster Keaton in The Three Ages. The story traces Keaton's attempts to woo a girl away from Beery in three different time periods: the modern day, ancient Rome, and the prehistoric days of cavemen and dinosaurs.

In the article "Wallace Beery Makes Sacrifice for 'Lost World'" (June 23, 1925), the Los Angeles Times reported a tale of daring reminiscent of Malone’s first meeting with Challenger: “They broke the new [sic] to Wallace Beery by letter because nobody had the nerve to tell it to him personally. He had to have curly hair for his role in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s ‘The Lost World’… Beery’s hair is not naturally curly and he would not wear a wig in summer – not Wallace. A curling iron was the only way out.” (Jun 23, 1925)

Director Harry O. Hoyt.

You may not want this part of the movie ruined for you. If not, stop reading now. I mean it. Because otherwise, you're going to find out that the steamy jungle river that the expedition paddles down in their canoes was actually the flowing open sewer of Los Angeles, which marked the border of MGM’s studio in nearby Culver City. Not letting the opportunity pass by, the effluent was bordered by prop trees and foliage, providing a suitable Amazon River for the expedition to be menaced by a tree-bound python.

|

Wallace Beery, Lewis Stone, Bessie Love and Lloyd Hughes. In a trend that would continue throughout dinosaur cinema, it was obvious that the dinosaurs we’re going to be the stars of The Lost World. Unique amongst dinosaur films, even to this day, The Lost World’s dinosaurs were shown as real animals in a real ecosystem… The carnivores terrorized the herbivores with at least as much zeal as they did the protagonists. However, documentary verisimilitude only goes so far in the nickleodeons of the 1920's, and the antediluvian monsters of Maple White Land would require a living Challenger Expedition to square off against. Filling their shoes were Wallace Beery, Lloyd Hughes, Bessie Love, Lewis Stone and Bull Montana, and they were joined by thousands of extras and a well developed cast of animal actors. During promotion for The Lost World, much was made of the fact that Wallace Beery (1885-1949) ran off to join the circus at age 16. Working with Ringling Brothers, Beery became the elephant keeper, but eventually decided to move to Broadway and Hollywood after a nearly lethal encounter with a leopard. A heavy-set and decidedly unattractive 6'1", Beery has predisposed to playing larger than life characters, including Professor Challenger.

Wallace Beery as Prof. George Edward Challenger. Lloyd Hughes (1897-1958) always was a reluctant leading man. His all-American good looks brought him out of the ranks of movie extras and into the limelight, but he never sat comfortably in it. According to his oftimes co-star Mary Astor: "Hughes was a nice guy who should never have been an actor and he knew it." This was even reflected in his fitting portrayal of reluctant adventurer Edward Malone, of which he was quoted as saying: ...there’s many a man occupying the pedestal of heroism who doesn’t know what it’s all about – save that he followed the bidding of the woman he loves… there’s many a poor devil who could be happy as the floorwalker of a department store, but is forced to go through life accepting the hero’s homage for something he did against his inner desires.The woman in question was Bessie Love (1898-1986), playing the invented role of Paula White. The daughter of a Texas cowboy turned Hollywood chiropractor, she was discovered by D.W. Griffith and one of her first roles was a small part in his legendary film Intolerance. In her autobiography, From Hollywood With Love, she voiced her philosophy that “success will never desert you if you can find exciting parts, however small: what is agony is to have the camera trained on you for five relentless reels when you have absolutely nothing to do but simper.” In an excellent example of art imitating life, actor Lewis Stone (1879-1953) practically was Lord John Roxton. After serving in the Spanish-American War and World War I, Stone translated his dashing, aristocratic good looks into a Hollywood career. A frequent romantic lead, he was perfectly suited to playing Conan Doyle's playboy hunter. It wasn't entirely easy going though, and Stone opined to the Los Angeles Times of June 21, 1925: Imagine trying to woo a girl in an unexplored region of South America, infested by prehistoric beasts, which should have been dead 10,000,000 years ago… What man can keep a girl’s thoughts on orange blossoms when a dinosaur as big as ten elephants is bearing down upon her with the intention of eating her for luncheon?Where Stone was typecast as the handsome romantic lead, poor Bull Montana (born Luigi Montagna, 1887-1950) was typecast playing apes. Five years before playing the Ape Man who created havoc for the Challenger Expedition, Montana played the very similar role of a murderous human brain transplanted into a gorilla’s body in Go and Get It. One of the final roles of his career would be as a monkey man in the first chapter of 1936’s Flash Gordon serial.

Promotional still photo. Animal actors found lucrative work in The Lost World, earning incredibly high salaries. Among these were a python, an alligator, spiders and termites and other assorted insects, a sloth, a bear cub masquerading as a “full grown” spectacle bear and Jocko the ring-tailed monkey. If the rent that the producers had to pay for the animals was aggregated to a yearly salary, the python would have earned $36,500, the monkey $14,600, the alligator $14,900, and the sloth $15,000. The insects didn’t require a big paycheck, but it’s unknown how much the poor fellow who had to go out and catch them received. Working with animals is always risky. Beery, Hughes and Stone were all insured by the producers against python bites, in anticipation of filming a scene that has since been lost. As Bessie Love recalls, working with the monkey posed particular problems: Did you ever work with a monkey? Don't. This tiny animal produced disasterous effects by ruining the clothes of whoever was holding him. He was palmed off from one to the other of us until he had been through the entire cast. When it came to my turn we had to re-take the scene. The director, Harry Hoyt, said to me, 'You mustn't show that you hate the animal.' 'I love the little thing,' I cried. 'I'm sorry to see it so unhappy with me.'

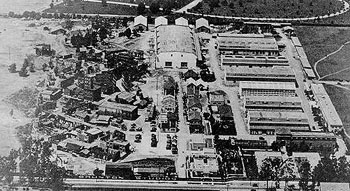

Bessie Love in a promotional picture. Later on set, the alligator tried to bite her. But there was still plenty of good fun to go around on set. Bessie Love described director Harry Hoyt as an “awfully nice man” who, In the scene where the prehistoric animals start to chase us, instead of yelling, 'Run!' he explained in detail why we should run run away from the enormous carnivorous tyrannosaurus, but we needn't fear the vegetarian brontosaurus... The animals were not actually on stage in this scene - they would be added later by double exposure - and it didn’t really matter if you called them Joe, Gus and Heimie so long as you looked terrified and scarpered. But Wallace Beery couldn’t pass up a chance like this. With the whole company standing around waiting for ‘Camera!’ he asked Mr. Hoyt, ‘Does the pterodactyl fly into this scene? No? Then would you just explain it again?’ And he would! Poor Mr. Hoyt. I'm sure he would laugh now. Joining the main cast and the animals were, reportedly, an additional 2000 extras, 200 automobiles and six omnibuses for the grand finale in the streets of London. The London sets themselves sprawled an eighth of a mile, while the jungle scenes included a shallow pool that housed the sleepy Amazonian village and the crocodiles and alligators swimming beneath it. Principle filming was done on First National's patch of the Brunton Studios, a Hollywood establishment renting soundstages and space for smaller studios without their own property. First National would move out into their own studios in 1926 and Brunton was then purchased by Paramount in 1927. The lot still exists today as the famous Paramount Studios on Melrose Avenue.

Brunton Studios in Hollywood. The live-action sequences finished filming in six to eight weeks. Bessie Love fondly remembered that, when the last shot was taken of the captured apatosaurus escaping down the Thames to the sea and freedom, thereby releasing us to go to other jobs, did we go home? Catch up on sleep? Certainly not! Everybody came to my dressing-room and we sat up the rest of the night complaining about the long working hours, the income tax, our agents, and hilariously reminiscing.

Promotional still photo. Review by Cory Gross.

|