|

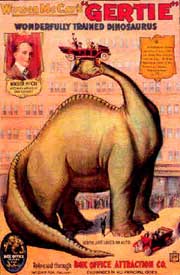

In 1915, the popularity of Gertie was so huge that John Bray released his own "version" of Gertie, featuring a brontosaurus of his own wreaking havok. Nowhere near as charming as the real Gertie, Bray's creation generally had a mean attitude. The real Gertie was just more curious, and happened to get the upper hand is all! John Bray was known for creating derivative films that were meant to cash in on the popularity of other movies. Even The Lost World itself wasn't safe, as Bray released The Lost Whirl in 1926. These sorts of movies helped to secure Bray's place as perhaps one of the fathers of exploitation B-films.

If you saw Jurassic Park (and who didn't?), you no doubt recall the "Mr. DNA" animated sequence, in which John Hammond interacts with the little redneck genetic fragment. While this was placed in the film to provide a quick and easy explanation for the genetic engineering angle of the film, it was also a tribute to Gertie the Dinosaur. Hammond does a vaudville-like performance similar to the one that Winsor McCay did with Gertie!

|

Dinosaur subjects go back almost as far as movie-making itself. Very early on, filmmakers caught on to the notion that somehow, it should be possible to replicate extinct enimals, enfleshed, on the silver screen... And that a public hungry for the exotic and novel would be willing to pay for it.

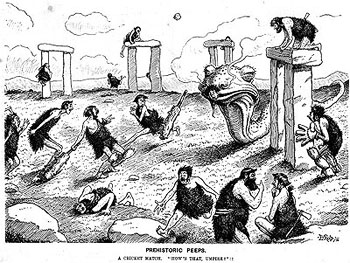

Unfortunately, the very early history of prehistoric cinema is lost to us. The first of these films is a now-lost short Prehistoric Man, of which next to nothing is know. This was joined in 1905 by Prehistoric Peeps, based on a cartoon series by E.T. Reed for the English periodical Punch. The humour of the Prehistoric Peeps was derived from primarily the same source as the more famous Flintstones: seeing modern habits and conveniences transposed into the antediluvian world of cavemen. This film adaptation of Prehistoric Peeps is a more straightforward example of Science Fiction, as a scientist falls asleep and dreams he is being chased around by saurian monsters and buxom cave women before being woken up in his fossiliferous laboratory by his assistant.

A Prehistoric Peeps cartoon from Punch about an ancient game of cricket at Stonehenge. In the same year that The Lost World novel was published, Hollywood director extraordinaire D.W. Griffith - responsible for the classics Birth of a Nation and Intolerance - tried his hand at dinosaurs and cavemen. 1912's Man's Genesis focussed on the hapless Weakhands who attempts to woo his ladylove Lillywhite from the crude Bruteforce. The title reflects both the emerging manhood of Weakhands and the development of modern man out of its prehistoric stock when the character invents the club, which in turn allows him to gain the upper hand on Bruteforce.

A scene from Brute Force. The 10 minute Man's Genesis was largely recycled in 1914 for Brute Force (also known as The Primitive Man). The story of Weakhands' discovery of the club is repeated and then expanded upon when he becomes head of the tribe, thanks to his technological prowess. Fending off dinosaurs of various types, from lizards in frills to life-sized paper mache, he also defends the women from the tribe of the villainous Monkeywalk. However, Monkeywalk's tribe also discovers the club, equalizing the prehistoric political landscape. But in history's first example of the arms race, Weakhands accidentally happens upon the bow and arrow (bypassing, apparently, the spear and the atlatl). This half-hour film was the longest dinosaur feature until the first full-length film, The Lost World in 1925.

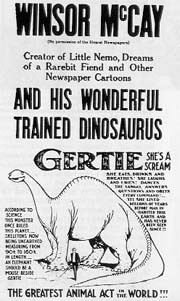

Gertie the Dinosaur meets a mammoth in a scene from her self-titled film. Also sometime in 1911 or 1912, Winsor McCay, the cartoonist famous for Dream of the Rarebit Fiend and Little Nemo in Slumberland, George McManus, creator of Let George do it, and several of their cartoonist friends took a automobile trip around New York. On event of flat tire, the group ventured into the American Museum of Natural History and pondered the life and habits of the dinosaurian beasts whose skeletons the museum housed. It was at this point that McCay bet McManus that he could restore the "Dinosaurus" to life... A bet McManus took up, sure that McCay was full of nonsense. Whether or not these events actually happened, the product of McCay's imagination was the first lady of dinosaur cinema, Gertie the Dinosaur. Like cinema itself two-dimensional animation was in its infancy, and McCay became one of its pioneers. Though often cited as the first ever animated cartoon, Gertie the Dinosaur actually falls a little short. The first was most likely Humorous Phases of Funny Faces in 1906. Winsor McCay himself created two previous animations in 1911's Little Nemo and 1912's How a Mosquito Operates. But Gertie does go down in history as the first animated character, preceeding the illustrious likes of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, Mickey Mouse, Felix the Cat, Betty Boop and Bugs Bunny. To bring their charming creation to life, McCay and his assistant John A. Fitzsimmons drew over 10,000 individual illustrations... completely redrawing each picture for each new frame, including the static backgrounds. It wasn't long before animation hit upon the technique of painting a single background for a scene and then illustrating the characters on clear celluloid. Not so in 1912. McCay and Fitzsimmons used rice paper to trace the background for each individual drawing, and then mounted that rice paper on sheets of carboard for filming. The finished Gertie was originally part of a Vaudville stage show in which McCay directed his dinosaur from stage right. In the 1912 Vaudville circuit of New York City, there would be regular programmes called "chalk talks" in which cartoonists would draw on stage from the suggestions of the audience. Deciding to up the proverbial ante on his peers, McCay introduced an illustration which could not only move and dance, but which would obey (or comically disobey) her artist. Not only could he command Gertie to hop from one foot to the other, or watch helplessly as she toyed with the small mammoth Jumbo, but he even did the amazing by throwing her food and then entering the picture himself! Of course, this was accomplished through careful timing, wherin McCay would throw a pumpkin behind the screen and as he did so, its animated counterpart would appear onscreen. The same applied for himself. The film promoted itself as the "Greatest Animal Act in the World", and included tag-lines like "Gertie: she's a scream. She eats, drinks and breathes! She laughs and cries. Dances the tango, answers questions and obeys every command! Yet, she lived millions of years before man inhabited this earth and has never been seen since!!" By 1914, the demand to see this novel film increased to the point where McCay created a version that included a live action segment that book-ended the cartoon. It was this segment that told the story of the bet and McCay's triumph over McManus. It also featured McCay's original Vaudville instructions to Gertie as intertitle cards.

The 1914 version of Gertie the Dinosaur. With her fame spreading, McCay included a gaggle of Gertie-like dinosaurs in a series of Little Nemo in Slumberland strips. Nemo and his friends come across the lost land of Antediluvia, where they run afoul of the natives and learn about their modern prehistoric conveniences. The Comic Strip Library has dutifully reprinted the full run.

A panel from Little Nemo in Slumberland. Gertie returned to the silver screen in 1921's Gertie on Tour, where she ran amok in the modern world. Travelling around the world, she had run-ins with various contraptions like trains and creatures like the modern small toad (you see, in her day, toads were huge, so the small ones frighten her). It ends with Gertie falling asleep and dreaming of the day when she was the life of the party, dancing amongst a group of brontosaurs. Unfortunately, this film is only known in fragments today, a good portion having been lost.

The remaining fragments of Gertie on Tour. Joining Gertie in the world of traditional animation would be a 1919 silhouette animation entitled Adam Raises Cain and two 1925 shorts, The Bonehead Age and Felix Trifles With Time, a Felix the Cat cartoon. Tony Sarg, the shadowpuppet animator behind Adam Raises Cain was tapped by producer Herbert Dawley to make The First Circus in 1921, utilizing the same style.

Felix Trifles with Time.

The First Circus. In 1915, a young dimensional animator by the name of Willis O'Brien broke onto the scene with a comedy short entitled The Dinosaur and the Missing Link. The original version of Missing Link was a relatively crude test reel which O'Bie (and he was known to his friends) created to experiment with and sell the technique of stop-motion animation to producers. Thomas Edison bought it, and commissioned O'Bie to produce a proper version of Dinosaur and the Missing Link, as well as Morpheus Mike, Prehistoric Poultry, Curious Pets of Our Ancestors and R.F.D. 10,000 B.C. between 1915 and 1917.

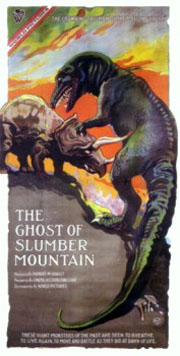

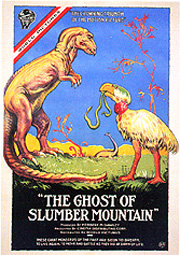

One of the titular characters from Dinosaur and the Missing Link. Like Prehistoric Peeps, the humour in O'Bie's series of stop-motion shorts comes by transposing modern problems and paradigms on prehistory. Sometimes, O'Bie goes the extra mile and makes his figurines sound practically aristocratic, like Missing Link's "Theophilus Ivoryhead", "The Duke" and "Miss Araminta Rockface". The more things change, the more they stay the same, and there isn't much difference between a dandy in a zoot suit or a fur loincloth. This series of comedy shorts led to a serious dinosaur film when Herbert Dawley hired O'Bie to animate his 19191 film Ghost of Slumber Mountain. O'Bie stayed in touch with famous fossil hunter Barnum Brown to ensure the accuracy of his dinosaur models, which added up to a full 45 minute film in which a man come upon the cabin of an eccentic palaeontologist. The ghost of this palaeontologist - who may have been played by O'Bie as well - exhorts the man to look through his special binocculars, which look into the deep past when saurians ruled the earth. Unfortunately for O'Bie, Dawley trimmed the original 45 minutes down to 16 minutes and proceeded to use much of that leftover material for a sequel in 1920 titled Along the Moonbeam Trail (Hawley didn't shy away from sentimental titles). Furthermore, while Slumber Mountain was successful, O'Bie's pay remained small and Dawley took all the credit for the animation. Years later, Dawley would all-but libel O'Bie in claiming: An employee of mine who learned the process by working in my office has been claiming, as employees sometimes do, that he did all the work and that the idea belongs to him and that sort of thing.It is understandable that Dawley should want all the credit, though. The animation was masterful, darkly atomspheric, scientifically accurate and quite durable. In 1923, it would be reused for the documentary Evolution. One can't help but wonder if he tried to lay claim to Tony Sarg's techniques as well. Not content to leave the comedy to the amateurs, Charlie Chaplin tried his hand at some slightly misogynist caveman comedy in 1914's His Prehsitoric Past, in which the Caveman tramp runs afoul of the tribe harem leader. Not to be outdone, Chaplain's main screen rival - Buster Keaton - released his The Three Ages in 1923, in which he attempts to woo the girl away from ruffian Wallace Beery across three time periods: 1923, Ancient Rome, and the Stone Age. Keaton made use of stop-motion for the dinosaur scenes that were missing in Chaplin's effort.

The Three Ages.

Inspiration for the multiple timeframe approach of The Three Ages was both artistic and practical. Artistically, the film was inspired by D.W. Griffith's masterpiece Intolerance, released in 1916. Subtitled Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages, Griffith's film spans four periods: Ancient Babylon, the life of Christ, the Hugenots and the modern day. The practical consideration is that The Three Ages marked Keaton's first feature film foray, and should it be less than successful, the three separate time periods could be spliced together into three separate shorts. Luckily it was a success, though it came in spite of co-star Margaret Leahy, an utterly incapable beauty contestant whose prize was to star in a Hollywood movie.

Buster Keaton and paramour in The Three Ages. With interest in stop-motion and dinosaurs abounding in 1923, due to The Three Ages and Evolution, the Pathé Review released the short Monsters of the Past. Not only did Monsters of the Past show stop-motion dinosaurs (abiet crude ones), but it also went behind the scenes to show sculptor Virginia May making and animating the clay models. Epic filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille utilized cavemen for a fantasy sequence in his society drama film Adam's Rib, also released in 1923. The contrived story revolves around an agricultural baron whose alienated wife seeks solace in the arms of a deposed king. In order to win his wife back, the husband (played by Milton Sills, who would later appear in adverisements for Bob Sherms' Lost World-themed puzzle in 1925) uses his fortune to try and gain the king's throne back while their daughter attempts to redeem her mother's name by implicating her self with the king, to the chagrin of her palaeontologist fiance. Somehow or other, a caveman scene was worked into this confusing mess. These films all paved the way for the first feature-length dinosaur film, when Watterson R. Rothacker hired Willis O'Brien to produce The Lost World. Review by Cory Gross.

|